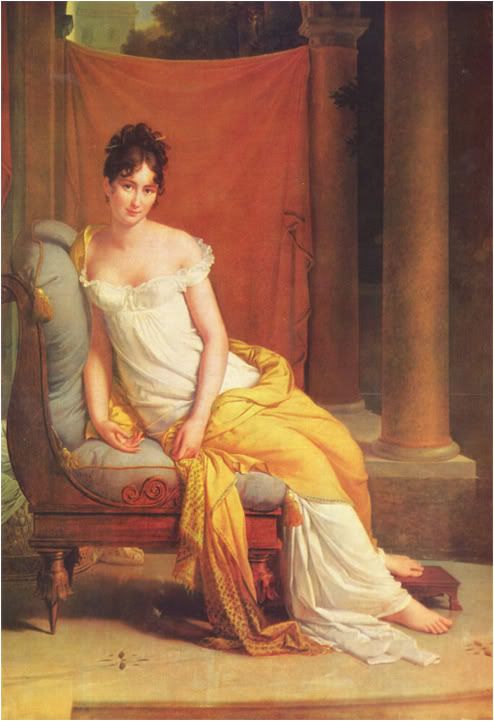

Portrait of Madame Juliette Recamier, by Jacques-Louis David (1800) The Louvre.

Today marks the quasi-bicentenary of the almost-completion of one of history’s great paintings. On September 28, 1800, France’s most celebrated painter, Jacques-Louis David, wrote to France’s most famous society beauty, Juliette Recamier, explaining that although he was having difficulty finishing his portrait of her he remained confident that the end result would “delight the whole world”. Madame Recamier, who had never been noted for her patience, was not at all pleased by this news. She became still less so when she went to the artist’s studio to check on his progress. David’s compelling but chilly depiction of her as a modern vestal virgin was not to her taste. She promptly commissioned a second portrait of herself from one of the artist’s pupils, the accomplished and amenable Baron Francois Gerard. For his part, David revenged himself on an ungrateful sitter by refusing either to finish or to release the picture which had failed to live up to her expectations. When pressed he responded with the following, superb reproof: “Madame, ladies have their caprices; so do painters. Allow me to satisfy mine; I shall keep your portrait in its present state.” The picture remained in his studio until the year of his death, 1826, when it was purchased by the state. It has been in the Louvre ever since.

What was it about David’s picture that so offended Juliette Recamier? According to the painter’s contemporary and biographer Etienne Delecluze, it was all to do with her feet. Madame Recamier, Delecluze suggested, had something of a complex about them. David had offended her by depicting them unshod. Joseph Turquan, the most floridly entertaining of Madame Recamier’s many biographers, added fuel to the fire of this particular speculation. “Her feet lacked fineness of proportion,” he wrote damningly. “They had been cast in a coarse mould.”

I went to the Louvre earlier this month to have another look at the picture and the aforementioned pedal extremities looked perfectly normal to me. I also took the opportunity of checking on Gerard’s replacement portrait of Madame Recamier, currently in the palace of Versailles. It is certainly very different, making her seem much warmer and more winningly flirtatious. But it too shows her barefoot; so given that she simply adored Gerard’s painting, naked tootsies and all, it seems unlikely that the feet in David’s masterpiece were really the root of the problem.

Portrait of Madame Juliette Recamier, by François Pascal Simon, Baron Gérard, (1802) Musée Carnavalet, Paris (current location)

Madame Recamier was a fascinating, mysterious and distinctly unusual individual. Brought up in a convent in Lyons she was married off at the age of 16 to a wealthy banker in his forties, who installed her in one of the most splendid and luxurious hotels de ville in Paris. But their union was never consummated, and the rumour was spread that Monsieur Recamier was actually his young bride’s unacknowledged father. As if to recompense herself for the aridity of her marriage, Madame Recamier used her flawless good looks to induce scores of young (and not-so-young) men to fall in love with her. Her numerous conquests included Eugene de Beauharnais, Benjamin Constant, Prince Augustus of Prussia and Chateaubriand. But to none of her amours did she ever cede her “virtue”, maintaining her virginity until the end of her long life.

She came into her own during the period of the Directoire, when wealthy Parisians celebrated the end of the Terror with a succession of parties and festivals. Her contemporary Arsene Houssaye described her as “one of the neo-Greeks who escaped, half-naked but clothed in modesty, from the ruins of a bleeding Pompeii”; and Turquan gives this description of her triumphal progress through Longchamp one Sunday afternoon: “Madame Recamier appeared in an open carriage, clothed in the style of Aspasia, almost in a peplum, her sandalled feet on a tiger’s skin, her hair in ringlets over a snowy neck touched by the pale March sun. Her half-covered arms adorned with cameos, she passed among the incroyables like an idol.” Everywhere she went, she was mobbed, and the extravagant parties which she held in her magnificent mansion were so popular with the ruling elite that Napoleon joked about moving the seat of government to chez Recamier. But those who actually fell for her, especially those who did so in the belief that her trademark gown of virginal white was merely an article of fancy dress, found themselves sorely disappointed. At just about the time that David was painting his portrait, Napoleon’s brother, Lucien Bonaparte, was cursing her for having led him on: “If you absolutely decide that you will never give way to love, I hope that you will always enjoy that calm which seems to satisfy all your vows.”

David’s portrait suggests that, initially at least, he had a considerable amount of sympathy for Madame Recamier: too much, perhaps, for her liking. He has painted her not as she wanted to be seen, not as the sexually irresistible yet morally irreproachable creature of her own myth – for all that, consult the picture which Gerard painted to cheer her up – but as an altogether more human being. The dark corner of the studio in which he has had her pose on her flimsy chaise-longue is so forbiddingly Spartan in its unrelieved, undecorated bareness that it resembles a prison more than a boudoir. It makes her terribly isolated. She looks as if she has been immured and even the tall, spindly, guttering lamp which stands beside her is like the mute accessory at the scene of a crime. Extinct as it is, it seems to symbolise the stifled passions of the dedicated coquette, as well as to stand in some way – in its attenuated, Giacometti thinness and isolation – for the profound loneliness of that life. There is a touching vulnerability in the expression on Madame Recamier’s face, as if somewhere inside she is really not quite sure about this bizarre role that she has found herself playing. She is a peculiarly uncertain femme fatale: a woman addicted to the pleasure she derived from the attention of men but incapable – or frightened – of responding to it. Such was David’s view, at any rate, and it is one which most accounts of her life seem to substantiate. By leaving the work to posterity “in its present state” the painter preserved, forever, the intensity of his own first impressions of her. She has made her own chaise-longue and now she will have to lie on it.

Andrew Graham Dixon

24-09-2000