The respective fortunes of the two nations during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are symbolized by dominant military leaders and adversaries, and indeed by the battles they fought. Napoleon Bonaparte and Horatio Nelson have become synonymous with power and represent the apotheosis of imperial splendour. It is not surprising that Paris has its Gare d'Austerlitz while London has Trafalgar Square. What better way of reinforcing the present and determining the future than by commemorating the glories of the past?

Antoine-Jean Gros - 'The Battle of Aboukir'

Antoine-Jean Gros - 'Napoleon at the Battle of Eylau'

The French Revolution emboldened intellectual life and soon found expression in the arts where simplicity and austere grandeur marked political and artistic endeavours. In the aftermath of the Revolution, French leadership recognized the importance of art for political propaganda none more so than Napoleon who would dominate much of the art produced during this period. By 1799, Napoleon had risen from successful military leader to First Consul and virtual dictator. The Revolution and the Empire had systematically used art for the propagation of their ideologies and the commemoration of their achievements. Construction of the Arc de Triomphe at Place de Carrousel began during Napoleon's reign. Patterned after the Arch of Constantine in Rome, it is an excellent example of 'monument propaganda'.

The magnificent art collection in the Chateau de Versailles contains numerous examples of the systematic use of art for the propagation of revolutionary' ideologies and the commemoration of their achievements. The leading artist was Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), named premier peintre of the Empire. The so-called School of David, consisting of painters who had either been trained in his studio or who imitated his style, formed the most prestigious group of artists in Europe during the Empire (1804-14). David's influence was far-reaching. His followers continued his precepts well into the new century and disseminated them beyond the borders of France. Napoleon's patronage gave their works prestige and institutional backing and the official biennial exhibitions, the Paris Salon, gave them international visibility. Under the direction of Vivant Denon (1747-1825), Napoleon's director of artistic patronage, a cohort of official artists was assigned to produce works of art that celebrated Napoleonic triumphs.

Francois Pascal Gerard - 'Battle of Austerlitz'

The regime was determined to commemorate its power, not least the power of military victory and imperial aggrandisement. Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835) was one of the most talented of David's immediate followers and during the years of the Empire was constantly employed to paint battles and military portraits. 'The Battle of Aboukir' (1806) commemorated the Egyptian campaign, while 'Napoleon at the Battle of Eylau' (1808) depicts Napoleon's visit to the battlefield in Prussia the morning after the slaughter (February 9th, 1807). Confronted by the horror of 25,000 dead and wounded soldiers scattered across the snow, Napoleon is alleged to have remarked: 'If all the kings of this earth could see this spectacle, they would be less eager for war and conquest'. Framed by the devastation of war--smouldering buildings and a ravaged countryside--Napoleon, clad in a grey silk coat lined with fur, is placed centre-stage on horse-back, with all eyes focusing on him. He extends his arm and raises his eyes in an expression of compassion. Gros' painting reflects the Emperor's self-image in a dramatic portrayal of a warrior monarch acting out the role of Prince of Peace.

Another pupil of David, Francois Pascal Gerard (1770-1837), exhibited his 'Battle of Austerlitz' (1810), a huge canvas originally destined to decorate the ceiling of the chamber of the Council of State. In this congested composition, Napoleon receives the banners of the Russian Imperial Guard. This was Gerard's bid for recognition as a painter of military history. It is a painting of individual mastery capturing the insouciance of the Emperor in his moment of supreme military triumph. It is also a propaganda artefact that retrospectively recorded Bonapartist, and by extension, French power. As a propaganda tool it was intended for the rest of Europe as much as for France. 'Moi aussi, j'ai ete frappe Austerlitz', William Pitt, the British prime minister, is said to have declared before he died.

Jacques-Louis David - 'Coronation'

Jacques-Louis David - Study of the 'Presentation of the Eagle Standards'

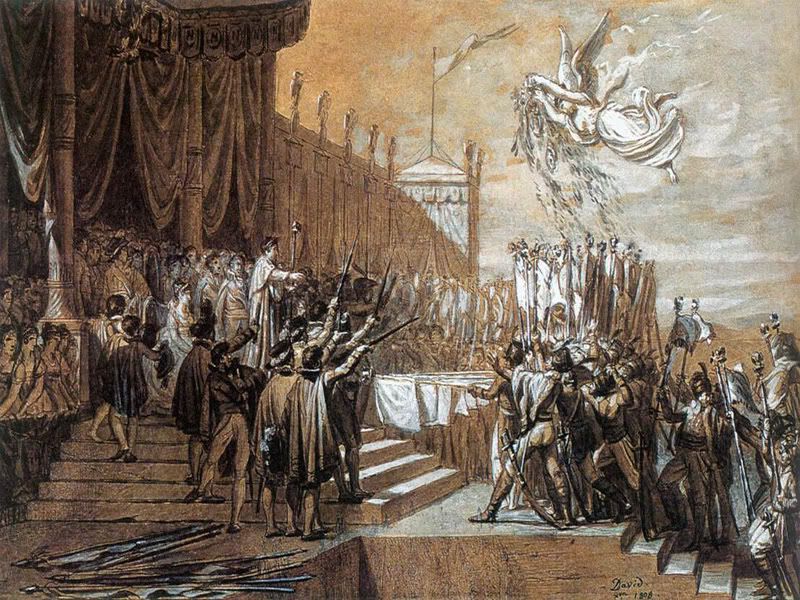

Such a warrior Emperor required the trappings of wealth and power and, as a result, Europe's artistic treasures were looted to glorify the new centre of power. The 'spoils of war' were not intended to encourage moderation but rather to proclaim the benefits of Napoleonic power and aggression. Some of the most celebrated examples in painting of imperial pretension are those of Jacques-Louis David. There is the depiction of Napoleon crowning himself during his consecration as Emperor in Notre Dame, December 2nd, 1804, watched by Pope Pius VII ('Coronation', 1805-08). The painting gives full play to the symbolism and imagery Napoleon was keen to manipulate. The 'Presentation of the Eagle Standards' (1808-10) records the swearing in of the army at the Ecole Militaire several days after the coronation.

Jacques-Louis David - 'Presentation of the Eagle Standards'

Jacques-Louis David - 'Bonaparte Crossing the Great St Bernard Pass'

Flanked by his marshals, Napoleon is shown pronouncing the formula of the oath 'to guard the Eagles and maintain them on the road to victory' as the colonels of the regiments rush up the steps of the tribune, dipping their standards and repeating the oath. This grandiloquent picture, in which some of the characters are depicted almost as antique statues, was not entirely to the Emperor's liking. Before the picture could be exhibited, David had to remove Josephine who had been replaced as Empress by Marie Louise in 1810. Thirdly there is David's famous 'Bonaparte Crossing the Great St Bernard Pass' (1801), where he is shown following in the footsteps of Hannibal and Charlemagne. Napoleon was happy to be associated in this way with great leaders of the past.

As Napoleon continued to dominate the continent, so he also dominated the European imagination. It is said that when Napoleon's army was in Boulogne, preparing for the invasion of England, English mothers disciplined recalcitrant children by threatening that 'Boney' would take them away unless they behaved. English satirists such as James Gillray (1757-1815) were quick to lampoon him. In his drawing of the 'Treaty of Amiens' (1802),--'the first kiss in ten years' between Britain and France--Gillray depicted Napoleon as a fickle and deceitful partner that could not be trusted. Some years later in 'War, the Exile and the Rock Limpet' (1842), J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) recalled Napoleon's exile on the remote island of St Helena, where he died in 1821. Exhibited shortly after Napoleon's corpse was interred with extravagant pomp and ceremony at Les Invalides, Turner depicted, in unflattering terms, a spindly, brooding Emperor surrounded by an angry crimson sunset that suggests the bloodshed associated in British eyes with Napoleon's campaign to subdue Europe by force.

James Gillray- 'Treaty of Amiens'

J.M.W. Turner - 'War, the Exile and the Rock Limpet'

David Wilkie - Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22nd, 1815, Announcing the Battle of Waterloo'

The English fascination with Napoleon did not, however, extend to commissioning canvases of his exploits. While David and his school in France were commemorating the achievements of the Napoleonic regime, England remained obsessed with its own national identity and version of these events. The Napoleonic Wars were later to loom large in the Victorian consciousness and a few artists never seemed to tire of painting Napoleonic campaigns, especially the Battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo.

Nevertheless, the status of battle painting as a genre remained the subject of some confusion. It is surprising to discover that, in the immediate aftermath of victory at Waterloo, there were no state projects for commemorative battle pictures, nor was there any increase in the number of battle paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy. There were, however, some note-worthy paintings depicting military themes. David Wilkie's 'Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22nd, 1815, Announcing the Battle of Waterloo' (1818-22) which was commissioned by the Duke of Wellington, was one of the most popular paintings in this genre, and when it was shown at the Royal Academy it required a barrier to protect it from the thronging crowds. Benjamin Robert Haydon's (1786-1846) enthusiasm was not confined to painting Napoleon as a prisoner-of-war; he painted twenty-five variants on the theme of 'Wellington Musing on the Field of Waterloo' including 'The Hero and His Horse on the Field of Waterloo', which inspired a poem by William Wordsworth. Two painters who specialized in Napoleonic campaigns were George Jones (1786-1869) and Thomas Jones Barker (1815-82), who studied in Paris under Horace Vernet. Jones painted numerous versions of the Battle of Waterloo, on one of which the Duke of Wellington is said to have remarked: 'too much smoke'.

Benjamin Robert Haydon - 'The Hero and His Horse on the Field of Waterloo'

Benjamin Robert Haydon- 'Wellington Musing on the Field of Waterloo'

Daniel Maclise's huge frieze-like murals painted on waterglass in the Houses of Parliament, 'The Meeting of Wellington and Blucher after the Battle of Waterloo' (1859-61) and 'The Death of Nelson' (completed in 1865) in the Royal Gallery of the House of Lords, enshrined for ever these two events in the nation's collective memory. The commemoration of two great British heroes provides the most striking examples of Maclise's command of large-scale complex figurative composition. Dante Gabriel Rossetti referred to them as a contemporary record of 'the legendary tire and contagious heart-pulse of hero-worship ... realized chronicles of heroic beauty'. Both paintings reflect a concern for the horror and pathos of war rather than jingoistic celebration. The paintings were conceived as part of an integral scheme for the Royal Gallery with the theme 'to the military history and glory of the country'. Most of the subjects chosen however were not battle pictures. Of the eighteen schemes only three showed a battle in progress, the majority illustrated some aspect of the aftermath of war.

The preponderance of tragic-heroic death scenes can be read as part of a wider discourse of anti-militarism that would later find resonance in the melancholy battle paintings of Elizabeth Butler. Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), the most popular British hero of early part of the Napoleonic Wars, was the supreme example of the tragic-heroic figure. A naval captain before he was twenty-one, he was a household name throughout most of Europe at thirty-nine and heroically killed in action three weeks before his forty-seventh birthday. His popularity extended to all sections of society and his naval exploits were commemorated in paintings, prints and all manner of souvenirs, and were celebrated in poetry and song. (His tempestuous and very public affair with Emma Hamilton, one of the most beautiful women of the day, was also lampooned in cartoons and caricatures.) His message to his fleet at Trafalgar, expressing his confidence that every man would do his duty, echoed down the years and his death became synonymous with the cult of sacrifice.

Daniel Maclise -'The Meeting of Wellington and Blucher after the Battle of Waterloo'

Daniel Maclise - 'The Death of Nelson'

Richard Westall - 'Nelson and the Bear'

Yet Nelson was not a conventional hero. A small man, his physical fragility and pallor compounded his heroism and bravery, contributing to the legend surrounding him. His body, with its shattered arm and blind eye--symbolized the blows aimed at Britain by its enemies. The artist Richard Westall attempted to capture this (retrospectively) in his painting 'Nelson and the Bear'. In 1773 Nelson had served as a midshipman on a Polar expedition to try to find a north-east passage to the Pacific. In this imaginary reconstruction the fourteen-year-old Nelson is alone on the ice cap confronted by a snarling polar bear. Despite being at a disadvantage, the fearless young sailor raises his musket to strike the bear. His ship, the Carcass can be seen in the background, firing the gun which eventually frightened the bear away. 'Nelson and the Bear' was commissioned by John M'Arthur, as a plate for The Life of Admiral Lord Nelson, which he wrote with James Stanier Clarke in 1809, and which was the first major biography of Nelson. Engraved by John Landseer, it formed part of a series of five painted for the book by Westall, all intended to show Nelson's life as a succession of heroic acts.

The best known painting of Nelson is probably Lemuel Abbot's half-portrait 'Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson, 1758-1805' replete with his gold epaulettes, the Nile decorations and pinned to his hat the distinctive diamond brooch ('Chelengk') given to him by the Sultan of Turkey in recognition of the victory of the Nile in 1798. The painting was based on a study made by Abbot at Greenwich hospital in 1797 while Nelson was recovering from the loss of his right arm. In what has become an enduring image of a legendary figure, Nelson looks confident and serene, but Abbot's painting commemorates both his bravery and his vulnerability.

Lemuel Abbot - 'Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson, 1758-1805'

Nelson's naval exploits were a favourite subject for painters and proved equally popular with the public. Typical is George Arnald's 'The Destruction of L'Orient at the Battle of the Nile', which shows the French flagship exploding at the climax of the night battle that began at sunset on August 1st, 1798. The Battle of the Nile had been Napoleon's first major reverse, and had given hope to a Europe shaken by his string of victories. Later, in his epic painting 'The Battle of Trafalgar' (1806), Turner captured the magnitude of Nelson's final victory, which was to maintain British maritime supremacy for more than a century. (An official Trafalgar poster of the time referred to it as: 'The most decisive and glorious Naval Victory that has ever been obtained'.) In the aftermath of the victory, the artist Joseph Dorffmeister painted a portrait of the defeated Emperor Napoleon turning his back on the English Channel and pointing towards his globe and alternative ambitions on the Continent after hearing news of Trafalgar.

Although the victory at Trafalgar was a cause for national celebration for Britain, it also resulted in the death of a towering heroic figure. Nelson was the only British war hero of his generation to be granted a state funeral. The national sense of grief at his death was on a scale and intensity unequalled until the assassination of President Kennedy in the US more than a century and a half later, according to Tom Pocock, a leading authority on Nelson. Immediately after Nelson's death there was a huge demand for images of the hero. The manner of his death and the romanticism of his life inspired artists, engravers, potters and manufacturers of commemorative trinkets.

George Arnald - 'The Destruction of L'Orient at the Battle of the Nile'

Denis Dighton - 'The Fall of Nelson'

Depictions of his death took two forms: some artists chose to capture Nelson's dying moments while others employed Christian imagery to suggest apotheosis and immortality. The two approaches--one historical and the other mythical--occasionally become intertwined. The moment when Nelson was fatally wounded on the deck of the Victory was captured posthumously by Denis Dighton in his dramatic and detailed 'The Fall of Nelson' (1825). In contrast, Arthur William Devis's intimate portrait 'The Death of Nelson' (1807), tenderly records Nelson's dying moments in the cockpit and the responses of the men hovering over him. Even more reverential is Benjamin West's 'The Death of Lord Nelson in the Cockpit of the Ship Victory'. Painted two years after the event, the artist evokes Christian imagery in a dark lamentation. The dying Nelson is laid out on the deck, his shirt is ripped open and he is draped in a white sheet. Behind is the Reverend Dr Scott, the ship's chaplain, leaning over Nelson to support his head. The Victory's surgeon, Dr Beatty, is holding a handkerchief over the wound. Bending forward and holding Nelson's left hand is Captain Thomas Hardy. Nelson is bathed in a golden shaft of light in stark contrast to the darkness that envelops the rest of the scene. It is a dramatic, but quintessentially tragic scene that invites the viewer to identify with a moment where the deeply personal becomes part of national folklore.

Shortly before the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson and West are said to have found themselves sitting next to each other at a public dinner. Nelson mentioned that his favourite painting was West's 'Death of Wolfe' and asked why the artist had not produced more pictures of a similar kind. 'Because' said West, 'there are not more subjects'. Nelson is reported to have replied; 'Damn it! I did not think of that!' Nelson then asked West to drink a glass of champagne with him. 'My Lord,' ventured the artist, 'I fear that your own intrepidity may yet furnish me with another such scene, and if it should, I shall certainly avail myself of it.' 'Will you, Mr West?', said Nelson, 'Then I hope I shall die in the next battle.'

Arthur William Devis - 'The Death of Nelson'

Benjamin West - The Death of Lord Nelson in the Cockpit of the Ship Victory'

Benjamin West - 'Death of Wolfe

The conversation may be apocryphal, but West, like so many fashionable painters, took full advantage of Nelson's death to exploit its symbolic and dramatic possibilities. 'The Immortality of Nelson' (1808) is an extraordinarily detailed painting by West, showing Nelson, draped in a white shroud and lying on a bed of clouds with the gods, being offered up to a grieving Britannia by Neptune. Equally sumptuous is Scott Legrand's 'Apotheosis of Nelson' (c. 1805-18) that depicts a deified Nelson ascending into immortality among the gods on Olympus. At the bottom of the picture, on the deck of a ship, three grieving seamen witness the ascent while the battle rages around them. Nelson's hat and sword remain on the deck. Britannia kneels to the left, wearing a helmet, her arms outstretched imploringly. Neptune (the god of the sea) offers Nelson to Mars (the god of war). A female figure (Fame) holds a crown of stars as a symbol of immortality over Nelson's head. To one side is Hercules, representing physical strength, and Minerva personifying wisdom. Presiding above them all sits Jupiter on his throne. In an extraordinary error, the artist concealed Nelson's left arm while showing the right arm broadly gesturing, although this arm had been lost at Santa Cruz in 1797. Legrand rectified this mistake in a later version painted in 1818.

The development of the mythic status of Nelson was one of the most extraordinary phenomena of the nineteenth century. The number of paintings, monuments, prints and ballads of the legend were astonishing. Statues and memorials were commissioned in towns throughout the country. After Nelson was buried at St Paul's Cathedral, a life-sized wax effigy was commissioned to be displayed at Westminster Abbey to attract paying visitors. Made by the medallion-maker Catherine Andras, for whom Nelson had sat just before leaving London for the last time, it was so life-like that Emma Hamilton had wanted to kiss its lips.

Benjamin West - 'The Immortality of Nelson'

Scott Legrand - 'Apotheosis of Nelson'

Charles Locke Eastlake - 'Napoleon Bonaparte on Board the Bellerophon in Plymouth Sound'

It has been claimed that Trafalgar was the naval counterpart of Waterloo and that Nelson's victory made Waterloo possible ten years later. There is a poignant footnote to the lives and careers of Napoleon and Nelson that is captured in a painting undertaken shortly after Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of the Bellerophon on July 15th, 1815. In Sir Charles Locke Eastlake's painting, 'Napoleon Bonaparte on Board the Bellerophon in Plymouth Sound' (1815), a reflective Napoleon dominates the canvas as he looks beyond the viewer to long-term captivity. His right elbow leans below a Union flag underscoring British victory and his defeat. Contemporary accounts suggest that Napoleon regularly appeared on the gangway and obligingly posed for boats and sightseers who came to observe the ex-emperor. Eastlake's painting proved hugely popular when it was exhibited in London in 1815 and several certificates were issued to testify to the likeness of the painting to Napoleon. On August 4th, Napoleon was transferred to the Northumberland, which immediately sailed for St Helena. On the long voyage to the South Atlantic, he discussed naval tactics with his captors and examined the reasons for Britain's maritime supremacy. He also had a life of Nelson read to him on his journey into political exile.

The Napoleonic Wars created tension between France and Britain and heightened each country's sense of patriotism and national identity. Paintings of this period reveal a great deal about the history of each nation. They provide insights into the respective cultures, contemporary tastes and artistic styles. They also suggest something of the love-hate relationship that has shaped our history for so long and continues to this day. As such Austerlitz and Trafalgar (and Waterloo) have become 'historical' short-hand that immediately conjure up past glories, individual achievement and national aggrandisement. Commemorated in paintings, monuments, poems, street names, etc., they remain classic examples of 'living propaganda'.

David Welch

July 1, 2005